Apple has officially said goodbye to the iPod models. The company announced that it would stop making the iPod Touch. This ends a 20-year run for a product line that led to the creation of the iPhone and helped Silicon Valley become the centre of capitalism around the world.

The iPod has been in the Apple company’s business catalogue for twenty years, but streaming music via Apple Music and devices such as the iPhone and Apple Watch have relegated it to the background.

The combination of these services and products has prompted Apple to cease developing more iPod models.

The Ipod’s History

The iPod began with a simple goal: to produce a music product to encourage people to buy more Macintosh computers. It would change consumer electronics and the music business in a few years, making Apple the most valuable company in the world.

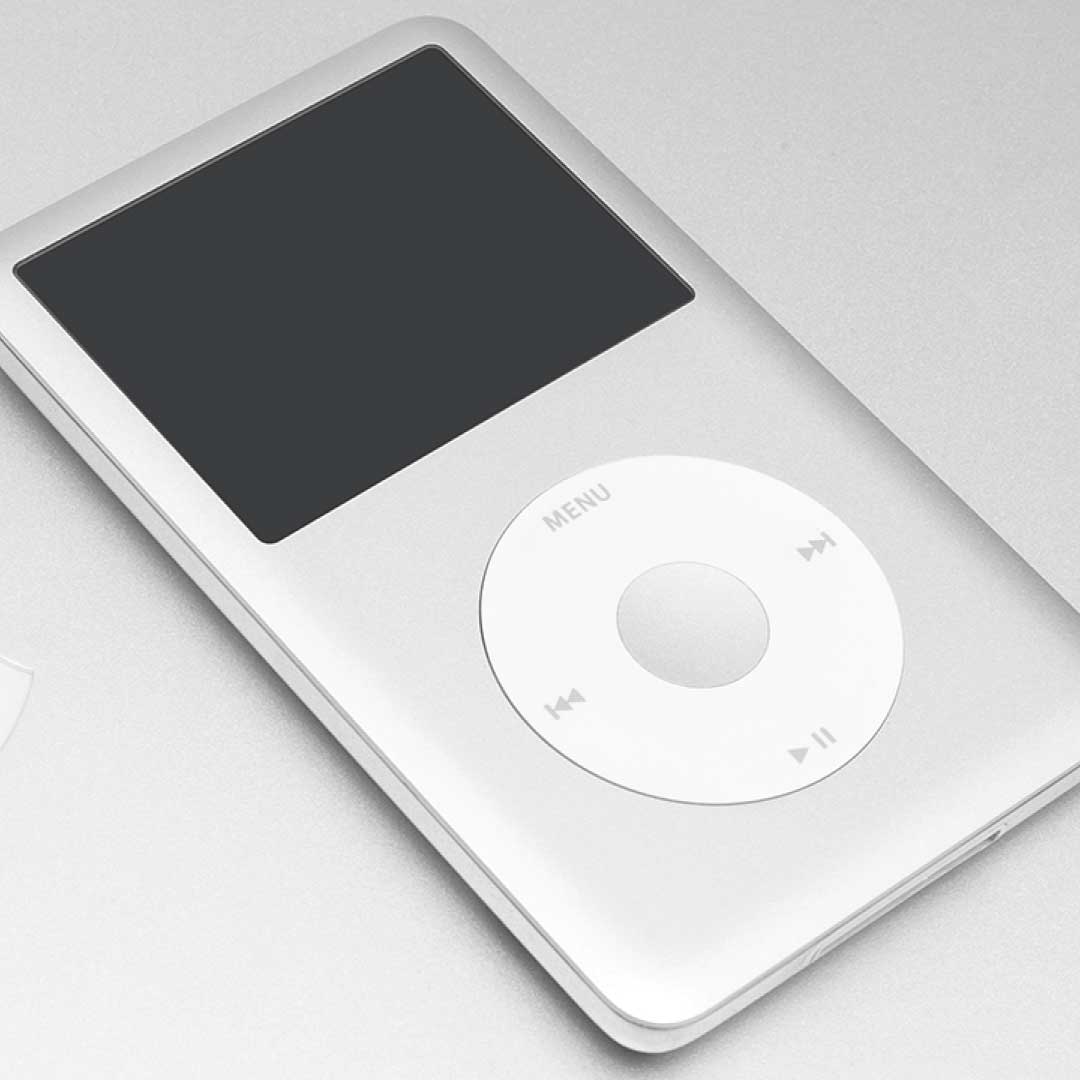

The pocket-size rectangle with a white face and polished steel frame first appeared in October 2001, weighing 6.5 ounces. It came with 1,000 tracks and white earbuds in a unique colour, moon grey.

Its popularity skyrocketed in the years that followed, giving birth to the iPod generation. People walked the world with headphones dangling from their ears for much of the 2000s. The iPod was everywhere.

According to Loup Ventures, a venture capital firm specialising in technical analysis, Apple has sold an estimated 450 million iPods since its introduction in 2001. It sold an estimated three million iPods last year, a fraction of the estimated 250 million iPhone sales.

Apple’s Position on Ipod

Apple told users that the music would live on, mainly through the iPhone, which it launched in 2007, and Apple Music, a seven-year-old service that reflects customers’ present tastes. Most people no longer buy and own 99-cent songs on their iPods. Instead, they pay a monthly fee to access much bigger music libraries.

For decades, the iPod served as a pattern for Apple, combining unequalled industrial design, hardware engineering, software development, and services. It also showed how the corporation frequently won despite rarely being the first to market with a new product.

The first digital music players began to appear in the late 1990s. People who were copying CDs onto computers at the time could put a few dozen songs on the first models to carry the music in their pockets.

Read Also : Pick n Pay raises the stakes for on-demand grocery delivery with Takealot partnership

Steve Jobs, who returned to Apple in 1997 after being fired more than a decade earlier, saw the burgeoning category as an opportunity to modernise Apple’s legacy computer industry. Mr. Jobs, a die-hard music fan who rated the Beatles and Bob Dylan among his favourite performers, believed that appealing to people’s love of music would help persuade them to move from Microsoft-powered personal computers, which had a more than 90 per cent market share.

“There was no need for market research,” claimed Jon Rubinstein, who led Apple’s engineering team. “Everyone was into music.”

During a trip to Japan, Rubinstein saw a new hard disc drive built by Toshiba, which sparked the product’s development. The 1.8-inch hard drive could hold 1,000 songs. In essence, it enabled the creation of a Sony Walkman-sized digital player with a far higher capacity than anything else on the market.

More on Ipod History

The creation of the iPod coincided with Apple’s acquisition of an MP3 software business that would become the foundation for iTunes, a digital jukebox that structured people’s music libraries so that they could rapidly make playlists and transfer songs. It helped Mr. Jobs realise his vision for how consumers would buy music in the digital age.

In a 2003 address, he said, “We think people want to buy their music on the internet by downloading it, just like they used to buy LPs, cassettes, and CDs.”

The $399 price tag of the first-generation iPod dampened demand, restricting the business to sales of less than 400,000 units in its first year. Three years later, Apple produced the iPod Mini, a 3.6-ounce metal case available in silver, gold, pink, blue, and green. It cost $249 and held 1,000 songs. Sales skyrocketed. It had sold 22.5 million iPods by the conclusion of its fiscal year in September 2005.

Apple increased the power of the iPod Mini by making iTunes available for Windows computers, allowing Apple to reach millions of new customers. Former executives said that Mr. Jobs turned down the idea at the time, even though it would later be seen as a brilliant financial move.

iPods were soon ubiquitous. “It took off like a rocket,” said Mr. Rubinstein.

Nonetheless, Mr. Jobs lobbied Apple to make the iPod smaller and more powerful. Mr. Rubinstein stated that the company discontinued production of its most popular product, the iPod Mini, to replace it with a thinner version dubbed the Nano, which began at $200. Over the next year, the Nano helped the company nearly treble its unit sales to 40 million.

Perhaps the most significant contribution of the iPod was its function as a platform for the birth of the iPhone. As mobile phone manufacturers began introducing music-playing devices, Apple executives were concerned about being outpaced by superior technology. If it was going to happen, Mr. Jobs decided that Apple should be the one to do it.

The iPhone drew on the same mix of software and services that helped the iPod flourish. The App Store, which allowed individuals to download and pay for applications and services, mirrored the success of iTunes, which allowed customers to back up their iPhones and put music on the device.

In 2007, the company dropped its long-standing corporate name, Apple Computer Inc., and became simply Apple, a six-year-in-the-making electronics giant.

“They showed the world they had an atomic bomb, and five years later, they had a nuclear arsenal,” said Talal Shamoon, CEO of Intertrust Technologies, a digital rights management company that worked with the music industry. “There was no doubt after that that Apple would own everybody.”